The Journal of Higher Criticism, vol. 12, no. 1, Spring 2006

Author Archives: Bob

Rehabilitating Judas Iscariot

The Huffington Post, January 23, 2006.

‘Trial Balloons’ to rehabilitate ‘Judas Iscariot’ (evidently emanating from Vatican ‘sources’) are presently in the news with predictable outcries from both ‘the Right’ and ‘the Left.’ While this kind of proposal is all to the good — regardless of the impact it might have on one’s ‘Faith’ — and, in view of all the unfortunate and cruel effects that have come from taking the picture of ‘Judas’ in Scripture seriously, very much to be desired (especially after the Holocaust); one must first look at the issue of whether there was ever a ‘Judas’ — to say nothing of all the insidious stories encapsulated under his name. Nor is this to say anything about the historicity of ‘Jesus’ in the first place or another, largely fictional character, very much now (in view of women’s issues) in vogue — his alleged consort and mother of his only child, the so-called ‘Mary Magdalene.’

But while this latter kind of storytelling does no one any specific harm historically speaking or, at least not one, one can readily identify; the case of ‘Judas’ is very different both in kind and in effect. It has had a more horrific and, in fact, totally unjustifiable historical effect and, even if it ever had happened the way Gospel and parallel tradition describe it, effects of this kind are wholly unjustified and reprehensible.

Email

Print

But in the case of ‘Judas’ there are only a few references to him and they are all clearly tendentious — for instance when he is made to complain about ‘Mary”s (another of these ubiquitous ‘Mary’s) anointing Jesus’ feet with precious spikenard ointment in terms of why was not this ‘sold for 300 dinars and given to the Poor’ (John 12:5 and pars.) — a variation on the ’30 Pieces of Silver’ he supposedly took for ‘betraying’ the Master in the Synoptics. But anyone familiar with this field would immediately recognize this allusion as but a thinly-veiled attack on ‘the Ebionites’ or that group of followers of ‘Jesus’ (or his brother ‘James’) in Palestine — and probably ‘the aboriginal Christians’ — who did not follow the doctrine of ‘the Supernatural Christ’ and saw Jesus as simply a ‘man’ or a ‘prophet,’ engendered by natural generation only and exceeding other men in the practice of Righteousness.

In fact, the Lukan version of his death and the Mattathean version do not agree with each other, a normal state of affairs where Gospel recounting is concerned, and the other two gospels do not mention either his death or how he died at all. The point, however, is that the whole character of ‘Judas Iscariot’ is generated out of whole cloth and it is meant to be. Moreover it is done in a totally malevolent way. The creators of this character and the traditions related to him knew what it was they were seeking to do and in this they have succeeded in a manner far beyond and that would have astonished even their hate-besotted brains.

Judas Iscariot is meant to be both hateful and hated — a diabolical character despised by all mankind and a byword for treachery and the opposite of all-perfection and the perfect, Gnosticizing Mystery figure embodied in the person of the ‘Salvation’ figure ‘Jesus’ — the name of whom even translates out into ‘Saviour.’ But in creating this character, the authors of these traditions and these ‘Gospels’ (often, it is difficult to decide which came first, either ‘the Gospels’ themselves or the traditions either inspired by or giving inspiration to them) had a dual purpose in mind and in this, as just signaled, he done his job admirably well.

His name very ‘Judas’ in that time and place was meant (as it is today) both to parody and heap abuse on two favorite characters of the Jews of the age, ‘Judas Maccabee,’ the hero of Hanukkah festivities to this day, and ‘Judas the Galilean,’ the legendary founder (described by Josephus) of what one might either wish to call ‘the Zealot’ or ‘the Galilean Movement’ (even, as we shall see below, ‘the Sicarii’) — and possibly even a third character, called in New Testament tradition ‘Judas the Zealot’ and very probably the third ‘brother’ of ‘Jesus’ known variously as ‘Judas of James,’ ‘Jude the brother of James,’ or ‘Judas Thomas.’ In fact, if he is ‘Judas of James,’ then he is also ‘Thaddaeus’ or ‘Theudas.’

Furthermore, the name ‘Jew’ in all languages actually comes from this biblical name ‘Judas’ or ‘Judah’ (‘Yehudah’), a fact not missed by the people at that time and not too misunderstood even today. So therefore the pejorative on ‘Judas’ or ‘Judah’ and the symbolic value of all that it signified in the First Century C.E. was not missed either by those who created this particular ‘blood libel’ or by all other future peoples even down to today. It is this the Vatican ‘trial balloons’ are obviously becoming sensitive of and, despite the theological risk involved and a predictable and largely negative outpouring of criticism which has followed, clearly want to try to rectify just as John XXIII did like-minded, similar ‘blood libels’ forty years ago; and it certainly is hard to imagine that such childish but diabolical story-telling could have had such a perverse and enduring effect for so long.

But there is another dimension to this particular ‘blood libel’ which has also not failed to leave its mark, historically speaking, on the peoples of the world and that is ‘Judas” second name or cognomen ‘Iscariot.’ No one has ever found the linguistic prototype or origin of this curious denominative in a manner that would satisfy everyone, but it is also not unremarkable that in the Gospel of John he is also called ‘Judas the son’ or ‘brother of Simon Iscariot’ and at one point even ‘Judas the Iscariot’ (John 6:71, 14:22, etc.). Of course, the closest cognate to any of these rephrasings is the well-known term used to designate (also pejoratively) ‘the Sicarii’ — the ‘iota’ and the ‘sigma’ of the Greek simply having been reversed, a common mistake in the transliteration of Semitic orthography into unrelated languages further afield like English, the ‘iota’ likewise too generating out of the ‘ios’ of the Greek singular ‘Sicarios.’

There is no other tenable approximation that this term could realistically allude to. Plus the attachment to it of the definite article ‘the,’ whether mistakenly or by design, just strengthens the conclusion. Furthermore Judas’ association in these episodes with the concept both of ‘the Poor’ (the name of the group led by James, Jesus’ brother, in First-Century Jerusalem) as well as that of a suicide of some kind in Matthew and in Acts (suicide being one of the tenets of the group, the Jewish First-Century historian, Josephus is identifying as carrying out such a procedure at the climax of well-known siege of the Fortress of Masada — to say nothing of the echo of the cognomen of the founder of this Party or ‘Orientation,’ the equally famous ‘Judas the Galilean’ or ‘Judas the Zealot’ also mentioned above) just strengthens this conclusion.

I have covered many of these matters in my book: James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Viking, 1997; Penguin, 1998) and will cover them further — along with other subjects — in the sequel: The New Testament Code: The Cup of the Lord, the Damascus Covenant, and the Blood of Christ, due to be published in May.

Equally germane is the fact that another ‘Apostle’ of ‘Jesus’ is supposed to have been called — at least according to Lukan Apostle lists — ‘Simon the Zealot’/’Simon Zelotes’ which, of course, also translates out in the jargon of the Gospel of John as ‘Simon Iscariot.’ Moreover, he was more than likely a ‘brother’ of the curious Disciple, already mentioned above, in the same lists known as ‘Judas of James,’ that is, ‘Judas the brother of James’ (the title by which he is designated in the New Testament Letter of Jude/Judas). In a variant manuscript of an early Syriac document, The Apostolic Constitutions, this individual is also designated ‘Judas the Zealot,’ thereby completing the circle of all these inter-related and overlapping terminologies which seem to have been coursing through so many of these early documents.

Of course, all these matters are fraught with difficulty, but once they are all weighed together there is hardly any escaping the fact that ‘Judas Iscariot ‘/’the Iscariot’/ ‘the brother’ or ‘son of Simon Iscariot’ in the Gospels and the Book of Acts is a polemical pejorative for many of these other characters meant to defame and polemically demonize a number of individuals seen as opposing the new ‘Pauline’ or more Greco-Roman esotericizing doctrine of the ‘Supernatural Christ.’ The presentation of this ‘Judas,’ polemicizing as it was, was probably never meant to take on the historical and theological dimensions it has, coursing through the last two thousand years and leading up to the present but with a stubborn toughness it has endured.

Nevertheless, its success as a demonizing pejorative has been monumental, a whole people having suffered the consequences of not only of seeing its own beloved heroes turned into demonaics but of being hunted down mercilessly to some extent the frightening result of its efficacy. If anything were a proof of the aphorism ‘Poetry is truer than history’ than this was As already remarked, I believe its original artificers would have been astonished by its incredible success. Even beyond this, not only is there no historical substance to the presentation or its after-effects, but if Jesus were alive today — whoever he was, historical or supernatural — he himself would be shocked at such vindictiveness and diabolically inspired hatred and he above all others would have expected his partisans to divest themselves of this single historical shibboleth anyhow.

Not only is a rehabilitation greatly in order in the light of the incredible atrocities committed over the last century (some as a consequence of this particular libel), but the process engendered by this historical polemic and reversal shows no sign of receding, the outcries over proposals to rehabilitate Judas themselves being evidence of this. It is yet another deleterious case of literature, cartoon, or lampoon being taken as history. In the light shed on these matters by the almost miraculous discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in our own time, it is time people really started to come to terms with the almost completely literary and ahistorical character of a large number of figures of the kind of this ‘Judas’ and, in the process, admit the historical error of malevolent-intentioned caricature and move forward into the amelioration of rehabilitation.

Fisk is Wrong on the West Bank

January 18, 2006.

Robert Fisk (“Telling it like it isn’t,” Los Angeles Times, 12/27/05) must be living in “cloud cuckoo-land.” He objects to alleged pro-Jewish and what he seems to imply as “pro-Israel” or “pro-Zionist” bias in U. S. newspapers. He wants the West Bank to be referred to as “Occupied Palestine” and objects to “Jewish” enclaves there being called “settlements,” “neighborhoods,” or “outposts” in the same manner that he does those who attack American forces in Iraq being called “terrorists,” “rebels,” or “remnants of the former regime.” Presumably he wants them to be called “patriots,” “nationalists,” or some other such honorable designation—again, in the same manner that he wants the Israeli presence on the West Bank ( there is no longer a presence in the Gaza Strip so we do not have to worry about that ) to be referred to as “colonies’!

When did “the Palestinians,” as he calls them, ever receive legal charter to the West Bank and when was it recognized by international law? Like it or not the “Jewish” claim was recognized (forget the Biblical one — presumably in his view the right of conquest gave the Muslim world a more recent one) by the Balfour Declaration in 1917 on the eve of the British conquest of the same and appended to the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in 1921, itself confirmed in the British Palestine Order-in-Council of 1922.

Though it is true that there was a later “Partition of Palestine,” adopted by the successor United Nations, in 1947, this was immediately rejected by all surrounding Arab States in 1948 (including it would appear by “the Palestinians” themselves) and, in fact, became a “dead letter” when the Jordanians (then the “Trans-Jordanians”) occupied the area and absorbed it in 1949 — a unilateral annexation objected to virtually by no one (at the time, hardly even “the Palestinians” themselves). Was this “Colonialism” by his definition? Did the West Bank and all that was constructed there by the “Trans-Jordanian Government” (now calling itself, therefore, “the Jordanian Government”) then become a Jordanian “Colony”?

Has he seen the pictures of “Palestine” in the Nineteenth Century? I refer him to such British travel writers as David Roberts in the 1820s and ’30s and Charles Wilson’s Ordinance Survey of Jerusalem in 1869 which show that the land was virtually deserted having been devastated by various wars and given over to what D. H. Lawerence would have called “the trump of the mosquito” (malaria). In fact, the census for Palestine which was reprinted in the classic 1905-6 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica shows Jews to have been a majority in Jerusalem to Muslims by about 60% to 25%, the rest being Christian, even at that time.

In other words, between the years 1917-18 and 1948, there was as much “Arab” immigration into Palestine as “Jewish,” presumably attracted by this increased prosperity as immigration always is — the only difference being that whereas the latter was well-documented and carefully watched, the former was not monitored at all since it occurred over what was on the whole a completely porous “inland” border. This is an incontrovertible fact because there was a period of economic prosperity caused as much by economically viable Jewish immigration into Palestine as a regular British administration.

I lived on “the West Bank” from 1968 to 1973 while I was writing my doctorate on Islamic Law in Palestine and Israel. There was no violence whatsoever. In fact, almost everyone I spoke with (except perhaps the upper classes who were losing their preferred status because of the widespread economic opportunities that had opened up for those who were willing to actually “work” for a living and join the competitive job market — a dirty word in quasi-feudal societies such as the one that previously operated and still operates on “the West Bank”) welcomed the Israeli presence. There was almost total “peacefulness” and you could walk almost anywhere without a weapon and even the thought of any danger. In fact, I was repeatedly admonished that the Israelis were too soft, much more so than the Jordanians had been when they were in control of the same areas who apparently really had acted like “Occupying Powers.”

The violence actually began after the Yom Kippur War with the Kissinger- and Carter-inspired “Sinai Accords” and withdrawals when everyone on the West Bank suddenly began to realize that the Israeli presence, which they had previously assumed in the normal manner was going to continue in perpetuity, was not going to be permanent and everyone knew what happened (and ultimately did happen) to people perceived as “collaborators” or being unduly too friendly with “the Occupying Powers.” It accelerated during the several “Intifadas” — themselves largely inspired by persons living outside the borders of “Palestine” who had not experienced the sudden upturn in the economy caused by a more normative “free enterprise” system and a greater degree of class equality. It reached a crescendo with the coming of “the Peace Process” when the “bully boys” and “thugs” (again largely from the outside) were armed to the teeth — and this by international fiat — and the present state of affairs we are all now a witness to began to develop in earnest.

So what is Robert Fisk talking about? The “living areas,” which he does not wish to even call “settlements,” were in almost all cases built upon unoccupied lands (actually, if the truth were out, these are more what should be called “suburbs,” “bedroom communities,” “small towns” — in the case of Maale Adumim, a big “town” — not “settlements”), what in strict Islamic Land Law is referred to as “Mewat” or “Dead Lands.” Just as in the American West, these carry a three-year right of revival, after which they can be owned having previously been “owned” by no one.

Do not “Jews” have a right to compete with “Arabs” or “Palestinians” in economic development or “Land revivification,” particularly in those areas which no one can deny were once their ancestral home in this area which for the last fifty (in fact, eighty) years has been in a kind of legal limbo? You mean there are to be “no go” areas or “ghettoes” where Jews are to be forbidden to own land in these areas? Is this what is being envisioned by the international community in all well-meaningness? Where has the legal status of any of these areas ever been ultimately regulated? Was not this what all the negotiations were supposed to be about? You mean, just as in Hitler’s Europe in the last century, there are now to be areas that are “Juden-rein” in the former areas of what we used to call by its Roman name, “Palestine”?

Who brought in the so-called “total failure of the human spirit” as Robert Fisk ends up referring to it as? Was it not the “bully boys” and “thugs” and, yes, those he refuses for the sake of preserving the purity of his own pristine conscience to refer to as “terrorists’? Why cannot everyone just co-exist and compete with each other peacefully in a spirit of free enterprise in these uncharted and uninhabited areas, as in suburban areas outside of settled areas anywhere in the world and let the best man, as it were, “win.”

Do you mean there is not enough financial power in the whole of the Arab world, to say nothing of the Islamic one, not to undertake this challenge to peaceful entrepreneurial competition in a spirit of true free enterprise? And if not, why not? Sadly, we all know the answer to that question. But what is Robert Fisk talking about? Isn’t he the one “Telling it like it isn’t”?

“‘Ad,’ ‘Thamud,’ ‘Hud,’ and ‘Salih’ as Reflecting Edessene/Northern Syrian Conversion Stories

Northern Syria as an Area for Many Language References at Qumran

Paper presented at the International Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Denver, 2005.

Northern Syria as an Area for Many Language References at Qumran

Broadcasting Interview by Rachel Kohn on her program “Spiritual Things” (ca. 2005): “Eisenman on the Scrolls”

Scandals and Rivalries of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Sunday 7 August 2005

Summary: Robert Eisenman reveals the scholarly jealousies that surrounded the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and, going back 2000 years, the religious rivalry between Paul and James, the brother of Jesus.

Program Transcript

Rachael Kohn: Two fragments of a 2,000-year-old Biblical scroll recently found in the Judean Desert have some people wondering if there are still more buried treasures. And if so, will they be the cause of another ‘academic scandal’?

Hello, I’m Rachael Kohn, and this is the Spirit of Things, on ABC Radio National.

The academic scandal of the 20th century is how one scholar described the handling of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Over a thousand ancient texts were discovered between 1947 and 1966, but not all of them were revealed to the public. It became almost a mission impossible for one man to force their release, Robert Eisenman.

Through his efforts all the Scrolls were finally published in 1991.

Meeting the gracious biblical scholar, Robert Eisenman, it’s hard to imagine that he’s considered an enfant terrible, but that probably has more to do with his scholarship on the early church. He claims that James, the brother of Jesus, was far more important than the Gospels lead us to believe.

I spoke to Robert Eisenman when he was visiting Australia recently.

Robert it’s great to have you here in Australia.

Robert Eisenman: It’s great to be here.

Rachael Kohn: Robert, would you say that the Dead Sea Scrolls was the single most important find in biblical scholarship?

Robert Eisenman: I think absolutely. I think the Dead Sea Scrolls are – it’s the finest, most miraculous find, because of the circumstances of their having been found to have been secreted or deposited in caves for 1900 or so years, and then to suddenly come to light in the middle of the Arab-Israeli War when the Jews have already just gone through a destructive Holocaust and are in the process of re-establishing themselves, to have these documents from their distant past come to light in 1947-48, if anything it’s a miracle, that is.

And I speak to Protestant, Catholic, Jewish audiences, Islamic audiences, and that’s the first miracle of God that I’m able to point out to them, the sudden appearance of these documents which are like a time capsule out of the past.

Rachael Kohn: When did you first get involved in the study of them?

Robert Eisenman: Well I was writing my PhD thesis in Israel, on Islamic Law of all things, in 1967 to 1971. I had done an MA in Hebrew Near East Studies, and I had had some courses on the Scrolls, four or five years before that. But I was continually going down to the Dead Sea because it’s so beautiful anyway, to visit the caves. And I became somewhat captivated by these Scrolls and the idea of them, just by visiting the physical locale of the Dead Sea.

Rachael Kohn: So you were a student when you first became acquainted with them. When did you become actually part of the Dead Sea Scrolls team of scholars?

Robert Eisenman: I never became part of the Dead Sea Scrolls team of scholars; this was a closed shop, and people from outlying districts were not allowed into the team of scholars, what we call the international team.

But I know that’s not the gist of your question. I will tell you that what happened was that after I left Israel, I went to California, which was completely new territory for me, and I went to a State university in California, which was really a people’s university. So at that university you met people who were interested in Jesus Christ mainly. That was the main interest at that time, The Late, Great Planet Earth and things of that kind. And so if you wanted your courses to go, you had to have bodies in them, and so you had to teach things that would excite or interest people with interests of that kind. This was a totally new experience for me.

So this was 1973, and I started teaching courses on the New Testament and on the historical Jesus, and I called one course, just to bring in students, ‘The Dead Sea Scrolls’. And then I ran, and started reading them as fast as I could and as deeply as I could. But when you teach these things over and over again, in conjunction with the historical Jesus, I developed another course called ‘Paul and James’. The reason for that was I read the Letter to the Galatians, I’d never read in graduate school, for the first time, and it blew my mind. I couldn’t believe the things that were being said in the Letter to the Galatians.

Rachael Kohn: Such as?

Robert Eisenman: Well mostly the confrontations between Paul and James. I didn’t even know there was such a person as James, I didn’t even know there was a brother of Jesus. And if you read Galatians 1 and 2, you know that Paul testifies directly to, ‘Of all the others in Jerusalem when I went there whom I saw, I saw none other but Cephas, or Peter, and James the brother of the Lord, which was the reason I was unknown by sight to the churches of Christ in Judea’. And just that statement alone in Chapter One of Galatians, where he contradicts everything Acts says, because Acts says that he was known, that he preached fearlessly and all the Apostles greeted him. And then in Chapter Two, it says ‘When the representatives of James came down to Antioch, or the party of the circumcision, as they’re called, Peter and Barnabas stopped keeping fellowship with Paul.’

Rachael Kohn: Now the party of the circumcision would refer to Christians or people who follow Jesus who practice circumcision.

Robert Eisenman: That’s not clear yet whether we’re getting converts coming in under circumcision, but certainly the party that’s demanding new converts be circumcised, come into the covenant first before they are heirs to the cover, where the Pauline groups would be claiming or making things a little bit more easier, if you want, and saying that you didn’t have to be circumcised. That’s a huge swath of my James the Brother of Jesus book, which is 1,000 pages long, on this very subject.

Rachael Kohn: Well it must have surprised you that James had been so sidelined, so pushed into the background in Christian thinking, and perhaps also in Jewish scholarship.

Robert Eisenman: Well I don’t know any Jewish scholars ever wrote about him, and in Christian scholarship, I rarely came across him. One of the reasons was that Luther was a pronounced anti-Jamesian. He didn’t think the Letter of James should even be in the New Testament. The problem for Luther was, it was too ‘Jewish’. Well that’s exactly the point, and in fact now that we’ve found the Dead Sea Scrolls, it became clear to me that the Letter of James had everything in common with the Dead Sea Scrolls, and nothing in common with what we now call Pauline Christianity at all.

Rachael Kohn: Are you actually drawing a connection then between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jamesian bloc of the followers of Jesus?

Robert Eisenman: Well, we’re getting ahead, but that’s the conclusion we’ll get to, but I would say that that’s what drew me into the study, that I began to see the parallels between the Jamesian community as such, and the Scrolls, and the closer you looked at them, the deeper the parallels went.

For instance, the ideological leader of the Dead Sea Scroll community, which we call Qumran by the Dead Sea, was a person known as The Righteous Teacher. They have this odd code, they don’t identify anyone, except for these odd codes, or the Teacher of Righteousness. And every time the Teacher of Righteousness is identified in the Dead Sea Scrolls, it’s to expound a passage, a Biblical passage having to do with the Zaddik, the key person in Jewish mysticism, or Kabbalah.

Rachael Kohn: That’s a Righteous Teacher, a Zaddik.

Robert Eisenman: A Zaddik, and in the scriptural passage it’s a Zaddik, the Righteous One; in the exposition it’s the Righteous Teacher, or the Teacher of Righteousness. They take this word from the scripture and they then expound it in the exegesis.

To go back to James and his community, this odd title James had in Latin, always, James the Just. Well I should bring that back through Greek into Hebrew, it goes dikaios into a Zaddik and you realise that a Zaddik was a name integral to James’ being in the tradition of this Christian church that we’re speaking of, so much so that scholars like Eusebius in the 4th century are calling him The Just One in place of his very name itself.

Rachael Kohn: Well how easy, or difficult, was it for you to pursue your studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls documents?

Robert Eisenman: Well that was the thing that started this whole agitation and campaign to free the Scrolls up. I went to Jerusalem in 1985, as a National Endowment for the Humanities Scholar at the Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, where the Scrolls first came in 1948, and where they were first photographed. And my project was to draw the comparisons between the community of James and the community at Qumran. And I found there was no work I could do there that I couldn’t do in California, because all the Scrolls were locked up tight. Every time I went to the person who ran the museum, a person called Magen Broshi, he would say, ‘Well we can’t do anything; go to the Scrolls team at the Ecole Biblique [et Archeologique Francaise de Jerusalem]’.

The Ecole Biblique were French Dominican friars, headed by at that time, Father Benoit, but previously Father de Vaux, and Father Milik, and they had the head of the international team, so-called, that the Jordanian government had set up to control the Scrolls. He would say, ‘Oh, we can’t do anything, go to the Israel Antiquities Department.’ So you’d go round in circles and round in circles, and it was just a game.

Rachael Kohn: Why couldn’t they do anything? What was it that they couldn’t do? They couldn’t allow you access?

Robert Eisenman: No, they wouldn’t, they wouldn’t allow anyone access. And Broshi told Philip Davies of Sheffield University, and myself, when we went in one day, he was trying to be helpful. He said, ‘You’ll never see the Scrolls in your lifetime’. And Philip Davies and I walked out of his office and said – that was 1986, the second part of our year there – Philip was with me that year, and we said, if I can be a little bit… well, we said ‘The hell you say, we will see these Scrolls.’ And then not four years later, we had all the Scrolls out.

Rachael Kohn: What was it that they were protecting? Was it their own reputations, did they want to be the first to translate the Scrolls? Was there dangerous material or revelations to be found there? What were they protecting?

Robert Eisenman: All of the above. But I’m not sure that they were aware of all these things. They were in fact doing that, but it wasn’t necessarily a conscious thing. I don’t give them credit for being that intelligent.

A lot of it was just human failing that happens in any activity where human beings build up monopolies. What happened was, when the Scrolls first came in, in 1947-48, when they were found in the midst of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the first cave that had fairly well preserved documents, we call it Cave 1, ultimately between ’47 and ’66, there were 11 manuscript-bearing caves found. But the public only knew about these documents in Cave 1, which were in jars, and that’s the famous story of the shepherd boy going in and finding the Scrolls in jars. They were fairly well preserved, about 10 or 12 Scrolls or so, and they went into the Israel Museum.

The Israel Museum didn’t try to make any capital out of them, and they were open to everybody. But the public at large didn’t know there were ten other caves found after the partition of Palestine from 1949 to 1966. And those are the Scrolls to which access was limited, and of course the Scrolls had been forgotten about by ’66.

Rachael Kohn: But they were under Jordanian rule.

Robert Eisenman: The partition had occurred and the Jordanian government set up an international team. This international team was headed by the French Dominican monk who was also very high up in Vatican political activity; he was on the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in the Vatican, and he got there because of his work on the Scrolls I think, and he was a very fine diplomat, Father de Vaux. His assistant, Father Milik really did all the work for him.

Father de Vaux lead the political interference, Father Milik did the vetting and stuff of the manuscripts and giving it out to people. But the committee that they established, there of course it was Judenrein, there were no Jews on it. And finally there were some Protestants, but ultimately they were constrained to the biblical manuscript, not the new manuscripts. The biblical texts were just versions of biblical documents we’d already known. But the interest was in about 1,200 new documents which we called sectarian or non-biblical texts. And those were carefully given out to selected people who could be trusted, and that’s what started the whole monopoly going.

Then, in 1952, the famous Communist fellow-traveller and literary scholar, Edmund Wilson, wrote a piece for the New Yorker magazine, and of course he was a fellow-traveller and Communist sympathiser, this threw kind of shivers into the Establishment, and what happened was, that frightened them because he suggested the Scrolls had some relation to Christian origins. I knew someone who was on the committee, a German scholar, who told me in no uncertain terms that he had done a lot of work for the people on the committee, that at that point basically the word went out, ‘Let’s go slow until the crazies go away.’

Rachael Kohn: Implying that Wilson was a crazy?

Robert Eisenman: Wilson and a lot of others. John Allegro for instance, and all the others with theories that didn’t agree with the Establishment work, instead of crazies. So a kind of curtain of secrecy came down, it was really feared. I don’t think it was something that they plotted or anything. The Ecole Biblique was established in the 19th century as an archaeological school that would interpret for the common masses the new results of archaeology, so they had a sort of role to play and they were playing that role. Well if they were going to be extremists, crazies, fanatics, other kinds of people, you know, weirdos if you like, interpreting these scrolls, that wasn’t what they were looking for.

Rachael Kohn: Robert Eisenman, the man who broke the gridlock on the Dead Sea Scrolls, and went on to use them in his groundbreaking study, James the Brother of Jesus.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, which were discovered between 1947 and 1966, have both illuminated the past and raised many questions. Who did they belong to, and what’s the nature of the sect that produced some of the scrolls? Is there a connection to the early church? Robert Eisenman has his own theories, but in order to prove them, he first had to wrest the Scrolls from a clique of scholars who were touchy about their contents.

Well this would have been a time shortly after the Nag Hammadi Documents were found; was there any overflow from that, the fear that the Nag Hammadi Documents, that is those that contained the Gnostic, so-called, Gnostic Gospels or Gnostic writings, which also seemed to present a very different kind of Christianity. Was the religious world sort of running scared at this time?

Robert Eisenman: I don’t think the Nag Hammadi things had entered the public consciousness in ’52 when this occurred. In fact I think, (I don’t have my date’s exact) but I think the Nag Hammadi texts were just being found around that time, and had that same problem in Nag Hammadi studies occurred, because James Robinson and my colleague at Claremont, had to break the log jam in the ’60s over the Nag Hammadi editing. There was the same resistance to editing those documents.

But I don’t think the public at large had grasped the Nag Hammadi significance until well into the ’60s and ’70s. So I don’t think that was impinging on what the Scroll problem was. What I think was happening with the Scroll problem was that when they went slow, and they only had a certain kind of people, and then John Allegro who was one of the only Protestants on the Scrolls Committee, who was dealing with sectarian texts, started to – he described in his book in 1956 called The Dead Sea Scrolls for Pelican Books, a little blue pocketbook, I think we all remember, he describes, (I saw his personal correspondence) how painful it was.

He knew about the ‘Copper Scroll’; the ‘Copper Scroll’ had been found. The ‘Copper Scroll’ was a list punched on copper of temple… hiding places of temple treasure. De Vaux and Milik refused to let him publish that in his book in 1956, even though he knew what was in it. And it was so painful to him until ten years later, when Milik finally edited the ‘Copper Scroll’, and then said it was a child’s exercise book, or something like that, that it wasn’t a real document.

Rachael Kohn: Yes, I mean there’s a lot of controversy about the way Allegro interpreted the ‘Copper Scroll’, and I think it’s still pretty much open to debate.

Robert Eisenman: Allegro was so upset that I think he really was driven insane. At the beginning, he asked the Jordanian monarchy to free the Scrolls and change the international team. Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, the same two writers who wrote Holy Blood, Holy Grail on which The Da Vinci Code has been based, wrote a book called The Dead Sea Scrolls Deception, with my help somewhat I must say, I was an unacknowledged covert third author of that book, though I don’t take responsibility for their ‘what if’ suppositions, or suggestive statements.

Rachael Kohn: Their conclusions, yes.

Robert Eisenman: Just to make sure that their data was correct. They’d covered this fairly well because they had access to Allegro’s letters from his wife, Joan, and he was, in 1966 just on the verge of getting the Jordanian government to take the Scrolls away from the international committee when in ’67 the Six Day War occurred.

The Israelis took the Rockefeller Museum in East Jerusalem where the Scrolls had been housed, and now they were presented with the problem of what to do with the Scrolls. They didn’t want trouble diplomatically in Rome and Europe, so they reconfirmed the international team just when Allegro was about to overturn it. And I think that drove him over the edge.

That also gave the international team another 20 years of life. And what these people on the international team did, well-meaning probably – it was a valuable product that they controlled. They were getting old, when they died or got too old, they passed it on to their favourite student, so you had a kind of monopoly, a dynasty, and they could make instant scholar superstars. If they gave an unknown manuscript out to a young scholar, that scholar would become famous overnight, editing a document that had never been seen before, for instance like the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice, basically a Jewish Kabbalistic document, and scholars like Norman Golb of Chicago, Roth and Driver at Oxford and many others had waited in line, and waited the whole time and never saw anything. No-one outside the Harvard/Ecole Biblique team were allowed to see anything.

Rachael Kohn: So you’re pointing to a situation that is like a time bomb ready to go off. People like you and Norman Golb were ready to explode and to –

Robert Eisenman: Well I don’t think Norman really accepted his fate when we came along, but he was happy that we were able to crack it.

Rachael Kohn: And how did you do that? How did you wrest the Scrolls from that clique?

Robert Eisenman: Well as I say, being out there, and I don’t want to take all the personal credit for it, but I think it was pretty much a one-man operation, I made the contact.

Rachael Kohn: This is almost like the Indiana Jones of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Robert Eisenman: Well there’s somewhat of that story I think. Others joined in, but the main thing was, I made the contacts necessary to get the negatives of the unpublished documents. I found the computer print-out in the Israel Antiquities Authority, that listed all of the documents, that they had there. Someone had made that available to me, and I couldn’t believe what they had. It was all on a computer print-out, and from there we were able to make official requests for plate numbers of documents that we didn’t even know existed. Like Philip Davies and I made a request in 1989 for all the unpublished fragments of the ‘Damascus Document’.

The ‘Damascus Document’ had been found at the Cairo Geniza back in 1897, and it was a very mysterious trail how it got there. So we wanted to see whether the Qumran parallels which were not in Cave 1, but however were in Cave 4 materials, which is the mother-lode of all the materials, but not as well preserved as Cave 1, we wanted to see if it agreed with the Cairo Geniza document or it didn’t agree, and we were denied.

Rachael Kohn: The Cairo Geniza was that storehouse of Hebrew manuscripts that two older English lady travellers had discovered it and told Solomon Schechter, the scholar at Oxford. Oxford? or Cambridge?

Robert Eisenman: He was at Cambridge at that time, yes.

Rachael Kohn: Cambridge. About them. So the ‘Damascus Document’ was published.

Robert Eisenman: He published it back in the 1890s, and you know, it was a legitimate concern. Are the Qumran fragments the same, are they different? So when we were denied that, I had the contacts, and I got all of the plates and the establishment realised that I had all of the plates.

In the meantime I had contacted James Robinson of Claremont who broke the Nag Hammadi roadblock, and I felt that it was good to have a Jewish and a Christian scholar involved in this, not just a one-sided aspect of this. And he’d love to come into it, because it meant another monopoly-breaking activity for him, and we set up a publication with E.J. Brill in Leiden, which is a famous scholarly publisher, which was to come out in April of 1991.

In the meantime, people got wind of it, went to Brill, put pressure on Brill and Brill backed out of this publication, and then made a different contract because everyone knew we had the pictures for that time, so the game was up. They made a different contract with the Israeli scholars who had by that time were coming in to do the same thing a couple of years later, publish all of the plates. A more official version, not a so-called pirated version, if you want to call it that.

And finally the Huntington Library, which is also up near James and myself in San Marino, California, realised they had a copy of all of the plates. There were four or five different copies that had been made in different places. I didn’t have access to the Huntington Library but they called me after our publication was cashiered in April of 1991, and my heart sank, because I knew we had missed the coup of the century. They asked me what they should do. They found that they had the same kind of pictures, should they publish? And I had to say to them Yes, do.

So I became their advisor, but they got tremendous credit for what they did, and our publication ended up in the lap of Hershel Shanks, the editor of the Biblical Archaeology Review, who held it back because he was involved in some other projects. And that came out then after the Huntington Library opened up their files, and so the facsimile edition did finally come out in November that year which led to a lawsuit in the Israeli courts.

Rachael Kohn: And how long did that last?

Robert Eisenman: Ten years.

Rachael Kohn: How was it resolved?

Robert Eisenman: In favour of the Israelis. [laughs] So I don’t want to bore your audience with the terrible details of this, but what happened was the publisher, Hershel Shanks, who many people know, he publishes a magazine called the Biblical Archaeology Review, had unbeknownst to Robinson and myself, we had only written a short little introduction of three pages, and just put the pictures out there saying Look, we want all scholars to be available, this to be available to all scholars, we want to level the playing field as it were, we want a thousand voices to sing.

Hershel Shanks then put in a publisher’s Foreword, an unheard-of publisher’s Foreword, of some 35 pages, which had secret letters that I had gotten from the Huntington Library facsimile, copies of threats from different sources, things, all personal things, that I would never have agreed to have put in any Foreword. But he didn’t show me the copy of the Foreword, he showed it to Robinson, who didn’t understand what these things were. And so I was never shown.

When I went to New York for the opening of this facsimile edition, I saw these things in the Foreword, I said, ‘Oh my God, what has he done to his book?’ (I used worse language than that, but I daren’t say it on your radio station). And then ultimately this drew a lawsuit in Israel, because one of the documents he had attached to his foreword was a copy of ‘MMT’. Now ‘MMT’ was one of the important documents that had not been published, that a huge storm had broken out anyway in Poland because someone had published it in Poland, and I knew very well that putting such a document anywhere would cause a lot of problems. And I believe that was done purposely. That’s a personal belief of mine.

Rachael Kohn: Can you explain the nature of what’s in ‘MMT’?

Robert Eisenman: ‘MMT’ is an actual personal letter from someone to someone, like Paul would write his communities. It’s a letter we think perhaps from someone like The Righteous Teacher to a king of some kind. It seems to be a royal personage telling him how to practice Judaism. And it’s in about eight copies which shows that it was an important letter for these people. I call it a Jamesian Letter to the Great King of the Peoples Beyond the Euphrates. That’s my title for it ultimately after I finally found out what was in it.

But it’s an actually staggering bit of material that had been kept under wraps, lock and key, for 30, 35 years. And controversy had already broken out concerning it. So for Shanks to have put a Hebrew copy of that in the publisher’s Foreword, that drew the ire of the people in Israel. And I well understood that. I didn’t even know it was in there until I went to Israel, but they wouldn’t believe this, and I was served with the papers. ‘You published ‘MMT’ [they said]. I said, ‘Why do I need to publish ‘MMT’? I’ve all the plates of ‘MMT’, [They said] ‘it’s in the Foreword’. I said, ‘Well, I never really looked that carefully because it was so upsetting to me.’ I looked at the Foreword, the attachments to the Foreword and there it was. And the Israel judge said ‘Eisenman and Robinson were the editors of this book, therefore they edited the publisher’s Foreword, therefore they’re liable for this.’ And we did not edit the publisher’s Foreword, and we never claimed to be editors, we said the book was prepared, the photographs were prepared with an introduction by us. But as that got translated into Hebrew, it became ‘edited’. And that’s the whole story.

Rachael Kohn: Well that’s not quite the whole story, at least not here on The Spirit of Things, where Robert Eisenman reveals his theory about the origins of Christianity, a story of rivalry, between Paul and James the Brother of Jesus. That’s coming up, but first here’s music of the Dead Sea Scrolls as re-imagined and recreated by Australian duo Kim Cunio and Heather Lee.

CHORAL

Rachael Kohn: Well now that these documents are available to everyone, or at least to those who have the languages and the expertise to translate them, they are open to all sorts of interpretation, some very highly informed, some rather bizarre. And I would imagine that at the moment, the opening up of the Dead Sea Scrolls has unleashed all sorts of strange publications.

Robert Eisenman: Well everyone in fact ultimately benefited from opening them up. The Establishment went on from six official volumes ofeditio princeps to some 26, that’s because they were now under the pressure. Also they expanded themselves astronomically. So they got their work done really quickly under Emmanuel Tov, and so on. That was a huge plus.

There were other bizarre theories and so on, but what we wanted to happen to some extent happened, although I don’t think it happened to the extent that I would have liked, to open up the study to many differing voices. I felt that what we had before us, I felt this before we opened it up, was the literature of the Messianic movement in Palestine, and not Essenes, not Christians as such, not Zealots as such, although all these groups could be considered under that rubric, because it was so Messianic. And that’s what had been missed previously. And we showed some new Messianic fragments that were utterly Messianic.

Why was that important? I mentioned my James connections that I had earlier seen, and James as the successor in Palestine. What we didn’t mention earlier was in the same Galatians, when the representatives of James come down called the party of the circumcision by Paul, Peter has to defer to James’ rulings. Peter and Barnabas are under James’ control. Paul is very bitter about this and spends the rest of the Galatians and part of I Corinthians and 2 Corinthians complaining bitterly about this. So James is clearly the leader of the early Christian church.

This doesn’t come out in Acts to any extent, and certainly the Gospels don’t give us any anticipation of this. So this James person is a person of really overweening authority, and as it turns out from the materials we have, we know more about James from non-biblical sources than any other character in early Christianity.

We have him in Josephus, the Jewish historian of the 1st century; we have him in the strange document called the Pseudo-Clementines as the leader; of course in the Nag Hammadi Scrolls he is a very important character. So we have him across a whole array, Eusebius, Epiphanius, Jerome, just a whole array of early church scholars and documents, the Gospel of Thomas, and so on.

Rachael Kohn: So where does Jesus fit in, in the early movement? Is it James or is it Jesus who is central to the Messianic movement? One would expect it’s Jesus.

Robert Eisenman: Well that’s what the historical Jesus is all about. If we knew who Jesus was, we wouldn’t have to have a quest for the historical Jesus that hasn’t been resolved over 200 years.

So there are a lot of questions, mainly relating to the Gospel presentation of who Jesus was, and I think that’s a retrospective presentation, to a certain extent within the eyeglasses, or through the spectrum of Pauline theology.

I sometimes call the character in the Gospels ‘Jesus Paul’, because the character there is against his own people often, he prefers Roman soldiers to ordinary Jews, he really doesn’t care about his family, ‘Who are my family, and my brothers to me?’ and so on. He doesn’t even seem to like Peter, because Peter sinks for lack of faith in the Sea of Galilee, Pauline faith that is. So people don’t realise a lot of this is polemical storytelling directed against another party. People take this as direct history.

What I’ve said is that people mistake literature for history. The Gospels are to some extent retrospective literature, like the Greek literary documents, with all the attributes of literature, raisings, curings, exorcisms, walking on water, multiplying loaves, all these things that are more literary things than historical, I think that scientifically minded people would consider historical.

So I say what we do is have to put all these things on the table. The Gospels, the extra biblical literature, the Nag Hammadi texts, early church texts, and the Scrolls. To my mind what the Scrolls are is a time capsule, a miraculous one. We didn’t know we would have the literature of the Messianic movement presented to us.

Now this movement is not Christian, and that’s why the early people who worked on the Scrolls didn’t really recognise it. Milik said these people would be Christian if they had a devout doctrine of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Well they didn’t, because it’s 1st century and there was no developed doctrine of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Those are the particular glasses he’s looking through.

Well these Scrolls are militant, uncompromising, apocalyptic, and they believe in righteousness but they don’t believe in loving their enemies. They hate their enemies. It says ‘Hate the sons of the pit’. So in a lot they were the reverse of almost everything, or vice versa, what we know of Christianity reverses almost everything, the whole ethos of the Scrolls. The Scrolls are purity minded, and what they’re doing is, they’re in the desert camps, they have the texts from early Christianity, like ‘Make a straight way in the wilderness’. This is what they claim they are doing in the wilderness in their desert camps. But what are the desert wilderness camps? They’re preparing the way for the final apocalyptic war against all evil on the earth which is to be led by the Messiah and the heavenly host. Well all these are what we know in Christianity as we know it, but our Christianity is more Paulinised. It’s gone overseas, it’s been Hellenised.

I say this is the ur Christianity, the native Palestinian Christianity, not yet Christianity, before it went overseas, and to my view this is led by James the brother of Jesus.

Rachael Kohn: And was there any role in that in your mind for Jesus?

Robert Eisenman: Yes there is. What does Paul know about Jesus? He knows maybe two facts about him, that he may have been crucified at some point, and that he had a brother called James. Other than that, he doesn’t seem to have any physical knowledge of Jesus’ existence. You would think someone who came in the mid-30s shortly after Jesus was purportedly crucified, would have a lot more information.

Now I don’t doubt there was an earlier crucified person of some kind, but I think that we need to decide what happened and who this person was. We have to go through the Scrolls, not through the Gospels, because to my mind, the Gospels are presenting their historical recreation through overseas eyes of what they think may have been, and it’s the total opposite of what the Scroll people would be presenting.

For instance, their Messiah sits with prostitutes, very famous, faces we all love; is a glutton, meaning he doesn’t keep dietary regulations; sits with tax collectors, and so on and so forth. Keeps company with the blind, the lame and the poor, and so on. Well we’re all very sympathetic to that, but those are just the categories in the ‘War Scroll’ that are barred from the wilderness camps, so I see these as polemical documents, one fighting the other.

And so where does this local Jesus fit in? I’ve said we know that Jesus had brothers. The question is, did the brothers have a Jesus? In other words, is the Jesus we have presented to us, a real Jesus or a Pauline reconstructed Jesus? And I think that the over-writing and the work through transmission that’s been done on that over two or three centuries, is so vast that we can’t penetrate that cloud. But what we can do is find the historical James.

Now I would say to your audience, that if things had been done and said in Jesus’ name that were not his, and we’ve seen things have occurred in the Middle Ages, the Inquisitions, the burnings, all these things that come from Paul’s letters, – ‘anyone who preaches a doctrine different from my own, let him be cursed’, Paul says twice and also in the Letter to the Galatians. And also Paul makes the blood libel, in Thessalonians 2:15, ‘the Jews who killed all of the Prophets’, which has gone into the Qur’an and we hear it endlessly from Muslim commentators now, ‘and killed the Lord Jesus’, etc. etc. etc., ‘they are the enemies of the whole human race’. It’s in Thessalonians, the first blood libel.

Well when things like that have become Scripture, they lead to Holocausts, they lead to hatred. So I think any really sincere believing person feels an obligation to get at the truth of this period. The Scrolls give us a tremendous window into the truth of this period. And my final conclusion on all these things is, that once you’ve found the historical James, you’ve in effect found the historical Jesus. Why?

Who would have known Jesus better? Someone who grew up with him, spent his whole early life with him, followed him? Or someone who was opposed to him, who had a Roman citizenship, who never knew him historically at all, who claims to have actually persecuted Christians unto death in his early career, and only knew Jesus as a supernatural being in heaven, a person he has mystical visions of, called Christ Jesus. Well the answer of any rational, modern person would be the former. But the answer of all history and our whole culture over the last 2,000 years, has been the latter. Now I think the Scrolls have come along to write that balance, and that’s what excites me so much about them.

Rachael Kohn: In Australia, we’ve had the works of Barbara Thiering, who has proposed that Qumran is actually a Christian sect, and she has placed John the Baptist there, she’s placed Jesus there. Are you also proposing that the Qumran community is in some way a Christian community, or is it something else?

Robert Eisenman: It is not a Christian community as such, it is a proto-Christian ‘community’.

If your listeners and readers and others would look at the book of Acts, they will see Christians were not called Christians according to Acts until Antioch in the mid-50s. That means they were called something else in Palestine before that, and we don’t even know if the ‘Christian’ language refers to any other community but a Pauline one, because that’s a Pauline community they’re talking about.

Well in Palestine I would say they were called either Essenes or Nazirites or some other like term. Now this goes back to the Essene terminology which the original scholars applied to the scrolls. They saw the Essenes as peace-loving, retiring, apolitical etc., but we have to define Essenes by what the Scrolls say. Now in the Scrolls they are not retiring, they are not peace-loving, they are extremely militant and apocalyptic.

There’s another testimony to Essenes in a 3rd century Christian scholar, probably based on a different version of Josephus, called Hippolytus. And he says there are two other kinds of Essenes, Zealot Essenes and Sicarii Essenes, meaning extremist Essenes and terrorist Essenes. And the terrorist Essenes will kill anyone they hear talking about the Law, who is not circumcised. In other words, they offer him, like in Islam, Islam or death, circumcision or death.

Now I’m not advocating this, but this brings us back to James’ party of the circumcision. So I would say that the Essenes are what Christianity was in Palestine before it went overseas and got Paulinised. So if Barbara Thiering is talking about a Paulinised Christianity, that never existed in Palestine per se. That was only overseas. In the Palestinian material, there were not two Messianisms in Palestine, there was only one. The one we have is in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Yes, John the Baptist is a kindred spirit to this militant Essenism; he is a militant character, even in the Gospel portrayal of him. But there’s a better portrayal of him in Josephus, and we even have the text, that the New Testament applies to John the Baptist in the ‘Community Rule’, that is, ‘make a straight way in the wilderness’.

But in the ‘Community Rule’ from Qumran, it’s repeated twice, and the first time it is interpreted in terms that ‘make a straight way in the wilderness’ means ‘separate yourselves from the community, be separated’ (I’ll get back to that in a moment). And the second part of this, the way in the wilderness is the study of Torah. Not the negation of Torah as in Paul and the way Jesus is presented in its own scripture. The second interpretation, said this is the time of the preparation of the way in the wilderness. This is the time of zeal for the law and the day of vengeance. That’s the end of the ‘Community Rule’. You couldn’t have a more militant presentation.

Let’s go back to the camps though, to my mind as I said, the Nazirites in the camps, the Dead Sea Scrolls community was a community of lifelong Nazirites, to some extent.

Rachael Kohn: Can you explain Nazarites?

Robert Eisenman: Well James is in all the early Christian texts, they say he’s a lifelong Nazirite. These are people totally dedicated to God, holy ones. And I think you can have gradations. Some lifelong, some less so. So that the lifelong ones, like James, seem to have also been vegetarians, which grows into a lot of modern affection for things like this. Now Paul hates vegetarianism. In Corinthians he says ‘Some people are so weak that they’ll only eat vegetables’, meaning attacking James. Some people are so weak that they are afraid of eating things sacrificed to idols. Now in the book of Acts, James’ rulings in Chapter 15 forbid Christian communities like Paul’s from eating things sacrificed to idols. So in I Corinthians Paul is attacking James on those issues, on eating things sacrificed to idols, which he says an idol is nothing in the world, and also on vegetarianism, so we have to see these polemics going back and forth, that’s how we can find James.

Rachael Kohn: But being vegetarian would mean that the community would also not be eating the meat sacrificed at the Temple.

Robert Eisenman: Well that’s – the extreme Nazirites were vegetarian. There are gradations. The lifelong Nazirites. That doesn’t mean they were all of that kind, some were lifelong, some were not lifelong. I think the extreme leadership would have been in that. But that’s a complicated question, and a very good one. They are pro-Temple, this group, but they want to eat in a purified Temple.

But I want to say just one last thing about this conflict of the way Paul presents things in the Book of Acts, which is basically a Paulinised book, and the James presentation. Peter’s a swing figure in Galatians 2, as I’ve already to some extent said, When the representatives of James come down, Peter stops keeping company with Paul, Paul complains bitterly, and Barnabas too, calls them both hypocrites. When Augustine wrote a letter to Jerome five centuries later, he said to Jermone, ‘How come Paul has the audacity to call Peter and Barnabas hypocrites?’ And Jerome couldn’t answer him on that question, it took a year and a half to answer him, and finally said, you shouldn’t inquire into things that are beyond your ability to deal with.

In any event in the Book of Acts is the key episode in the Paulinisation of Peter, this is when the tablecloth comes down from heaven with all the forbidden fruits. Peter says, ‘No Lord, no, I cannot eat these forbidden foods, I have never eaten any unclean thing.’ And then the voice cries out, three times, just like in the Gospels on Jesus’ death, like ‘when what the Lord has permitted, let no man set aside.’ And then Peter said, ‘I have now learned that I should not make distinctions between holy and profane, that I should not call any man or anything unclean’. Go to the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Dead Sea Scrolls in their wilderness camp ideology, speak of setting up the new covenant in the land of Damascus. In the land of Damascus, this new covenant, like the new covenant in the blood of Christ in the Scripture and in I Corinthians, this new covenant is to separate the holy things from the profane, to set the holy things up according to their precise specification, to separate thelahinazer, to be a Nazirite, to separate from polluted things. And so the whole ethos of Qumran is the opposite of the book of Acts, and that’s the point I am trying to make, that we have clear contradictions going back and forth that are clarified by these scrolls, and then your readers, your audience, have to decide where did Jesus stand on these issues?

I put Jesus as a Palestinian on the James side. Others of more faith and who desire to put in a more Hellenistic, mystery religion-oriented scenario, put him on the Paul side, the faith side, the side of beauty, denying all these purity regulations. But I feel that Palestine doesn’t demand that, and in fact would require something the opposite of that.

Rachael Kohn: What about sibling rivalry? Was the relationship between Jesus and James a good one?

Robert Eisenman: We have no indication that there was a negative one, except in the Gospels, which have an ideological axe on that score, to grind. In the Nag Hammadi texts, the Gnostic texts that you mention, there’s no indication of any alienation in those.

In the early church texts, there’s no indication I see whatsoever. The fact that James succeeds Jesus in the leadership… you see, the book of Acts says all the way through, which is why my James book is 1,000 pages long, James the Brother of Jesus, out here in Australia, in order to explain these things, all the way through to my mind, it is corrupting these early events, so that the election to replace James in early church literature, right after the death of Jesus, is replaced by the election, an innocuous election, to succeed Judas Iscariot, who has no significance and the person who was elected has no significance. And interestingly enough, if your readers or listeners look at it, the defeated candidate in Acts, and in the election, is somehow called Justice. The Just One.

So Acts is over and over again, giving its trail of clues, where the material is taking it, what material it is taking, and how it is transforming it and overriding and rewriting it, I show this over 1,000 pages in my James book.

So yes, to my mind Acts is the creation of Pauline Christianity as we know it, Paul is the hero of Acts. The Dead Sea Scrolls basically are the Jamesian form of, well, Messianism. I wouldn’t call it Christian, because I don’t think it was called Christianity at that point yet. And that’s where we have to decide. It’s tough, but I think it is a historical question that most people that live in the modern period would like to get their teeth into, they like challenges and they like to think they’re living in exciting times. This is probably one of the most exciting things that we can deal with in our lifetime.

Rachael Kohn: Well Robert, thank you so much for rescuing James out of the oblivion. You’ve brought him back to the fore.

Robert Eisenman: Well it’s my pleasure to have appeared with you and to have done something on behalf of James for bringing him back into people’s consciousness and awareness.

Rachael Kohn: The larger-than-life scholar with the larger-than-life theory, Robert Eisenman. Who knows, we might see a new church of ‘James the Brother of Jesus’. For Robert Eisenman that would more accurate, but from the sound of it, not necessarily desirable. He’s the author of James the Brother of Jesus, and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at California State University at Long Beach.

This week’s program was produced by me and Geoff Wood, with technical production by Angus Kingston.

Guests on this program:

Robert Eisenman is Chair of the Dept of Religious Studies and Professor of Middle East Religions and Culture at the California State University, Long Beach, USA. He is the author of many books including James the Brother of Jesus (1997) and The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered (1992).

MMT as Jamesian Letter to “The Great King of the Peoples Beyond the Euphrates”

The Journal of Higher Criticism vol. 11, no.1, Spring 2005.

An Esoteric Relation between Qumran’s “New Covenant in the Land of Damascus”

Revue de Qumran, vol. 21, no. 83, March 2004.

A Discovery That’s Just Too Perfect, Los Angeles Times, October 29, 2002.

Los Angeles Times, October 29, 2002.

James, the brother of Jesus, was so well known and important as a Jerusalem religious leader, according to 1st century sources, that taking the brother relationship seriously was perhaps the best confirmation that there ever was a historical Jesus.

Put another way, it was not whether Jesus had a brother, but rather whether the brother had a “Jesus.”

Now we are suddenly presented with this very “proof”: the discovery, allegedly near Jerusalem, of an ossuary inscribed in the Aramaic language used at that time, with “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus.” An ossuary is a stone box in which bones previously laid out in rock-cut tombs, such as those in the Gospels, were placed after they were retrieved by relatives or followers.

Why do I find this discovery suspicious? Aside from its sudden miraculous appearance, no confirmed provenance—that is, where it was found and where it has been all these years (from the photographic evidence it seems in remarkably good shape)—and no authenticated chain of custody or transmission, there is the nature of the inscription itself.

There is no problem getting hold of ossuaries from this period. They are plentiful in the Jerusalem area, most not even inscribed and some never used.

So confirmation of the Jerusalem origin of the stone is to no avail, nor particularly is the paleography. The Sorbonne paleographer Andre Lemaire authenticated the Aramaic inscription as from the year AD 63. What precision; but why 63? Because he knew from the 1st century Jewish historian Josephus that James died in AD 62.

The only really strong point the arguers for authenticity have is the so-called patina, which was measured at an Israeli laboratory and appears homogeneous. As this is a new science, it is hard for me to gauge its value. Still, the letters do seem unusually clear and incised and do not, at least in the photographs, show a significant amount of damage caused by the vicissitudes of time.

My main objection to the ossuary, however, is the nature of the inscription itself. I say this as someone who would like this artifact to be true, someone willing to be convinced. I would like the burial place of James to be found. But this box is just too pat, too perfect. In issues of antiquities verification, this is always a warning sign.

This inscription seems pointed not at an ancient audience, who would have known who James (or Jacob, his Hebrew/Aramaic name) was, but at a modern one. If this box had simply said “Jacob the son of Joseph,” it might pass muster. But ancient sources are not clear on who this Jacob’s father really was. If the inscription had said “James the son of Cleophas,” “Clopas or even “Alphaeus” (all three probably being interchangeable), I would have jumped for joy. But Joseph? This is what a modern audience, schooled in the Gospels, would expect, not an ancient one.

Then there is “the brother of Jesus” — almost no ancient source calls James this. This is what we moderns call him. Even Paul, our primary New Testament witness, calls him “James the brother of the Lord.” If the ossuary said something like “James the Zaddik” or “Just One,” which is how many referred to him, including Hegesippus from the 2nd century and Eusebius from the 4th, then I would have more willingly credited it. But to call him not only by his paternal but also his fraternal name, this I am unfamiliar with on any ossuary, and again it seems directly pointed at us.

This is what I mean by the formulation being too perfect. It just doesn’t ring true. To the modern ear, particularly the believer, perhaps. But to the ancient? Perhaps a later pilgrim from the 4th or 5th century might have described James in this way, but this is not what our paleographers are saying.

Finally, the numerous contemporary sources I have already referred to know the location of James’ burial site.

Hegesippus, a Palestinian native who lived perhaps 50 years after the events in question, tells us that James was buried where he was stoned beneath the pinnacle of the Temple in Jerusalem. Eusebius in the 4th century and Jerome in the 5th say the burial site with its marker was still there in their times.

No source, however, mentions an ossuary. Our creative artificers presumably never read any of these sources (nor beyond the first few chapters of my book) or they would have known better.

The James Ossuary: Is It Authentic?

Folia Orientalia, vol. 38, 2002.

Archaeological GPR investigations at Rennes-Le-Château, France.

From Jol, H.M., DeChaine, R.J. and Eisenman, R., 2002. Ninth International Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, Edited by S.K. Koppenjan and H. Lee, April 29 – May 2, Santa Barbara, CA, Proceedings of SPIE (the International Society for Optical Engineering), Vol. 4758: 125 – 129.

Introduction

The hillside town of Rennes-le-Château is located in Languedoc, southern France (Figure 1). The town has played a key historical role, both as the center of the Cathar heresy in the region and its subsequent suppression, as well as in traditions connected to the Templar movement and its ultimate suppression (Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln, 1996). Surface findings around the hilltop and the church suggest the area has long historical past including pre-Christian pagan religious sites and as a provincial center in the Greco-Roman period. More recently, the town has been linked by conspiracy and historical enigma buffs with numerous legends including the location of the Holy Grail, the Ark of Noah, the Ark of the Covenant and the treasures of the Temple of Solomon (Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln, 1996). Such mysteries and speculations have baffled and stimulated researchers for hundreds of years.

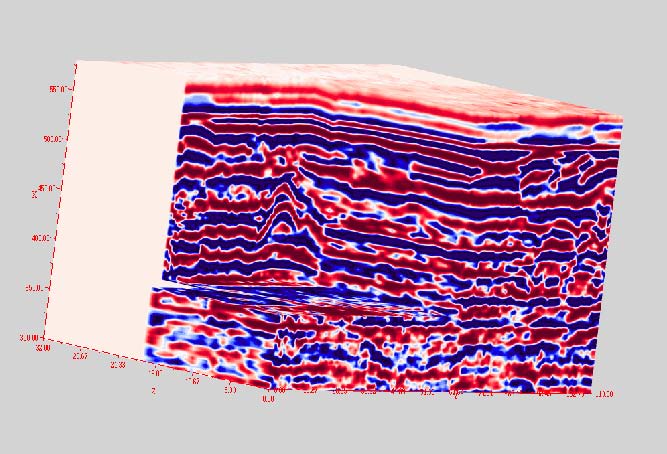

To explore some of these theories, a preliminary ground penetrating radar (GPR) investigation was undertaken. GPR is geophysical technique that has received growing recognition in its ability to detect and map buried archaeological sites in a safe, quick, and non-destructive manner (Sternberg and McGill, 1995; Kvamme, 2001). The GPR technique, which is based on the propagation and reflection of pulsed high frequency electromagnetic (EM) energy, can provide near surface, high resolution (dm to m scale), near continuous profiles of a site. Two locations were chosen for the initial GPR project within the town of Rennes-le-Château: the Tour Magdala and the Church of St. Mary Magdalen (Figures 2 and 3). The former in particular was the initial goal, since information had been conveyed of family traditions connected to a burial of interesting items in the tower at the time of its construction (J. Genibrel, personal communication, 2001). The survey at the Tour Magdala was carried out to image any features that may be located beneath the tower floor or around its outer base (Figure 2). The survey at the Church was carried out to map any features that may be located beneath the church floor (Figure 3). The reason for this survey was that the mayor of the town, Jean Francois L’Huilier, had himself wished that just such a investigation be undertaken, as he was convinced there may be interesting items beneath the present floor of the church (which probably was not the original church floor).

The central aim of the paper is to present the preliminary GPR results from two sites within the community of Rennes-le-Château, France – Tour Magdala and the Church of St. Mary Magdalen.

Figure 1: Map of Rennes-le-Cheateau and the surrounding area in southern France.

Fig. 1: Tour Magdala in Rennes-le-Chateau. GPR profiles were collected along the outer wall and within the cellar.

Methodology

With the availability of portable, robust and digital radar systems, GPR provides a noninvasive geophysical procedure that allows one to investigate the subsurface. The technique can be used to find the exact positions of buried items without disturbing the material above. The data presented were collected using pulseEKKO 100 and 1000 GPR systems with various antennae frequencies (ranging from 200MHz, 450 MHz and 900 MHz) and 200/400 V transmitters. Step sizes ranged from 0.05 m, 0.025 m to 0.1 m. To reduce data collection time, a backpack transport system carried the computer, console and battery. GPR profiles were collected along a single line and 3-D cubes were assembled from a series of 2-D GPR profiles that were collected running parallel to each other along an x-y grid system. The 2-D GPR profiles were initially processed and then interpolated to create 3-D datasets. Visual rendering of the 3-D datasets was done using Fortner T3D. Near surface velocity measurements were calculated from common midpoint (CMP) surveys. The application of radar stratigraphic analysis on the collected data provided the framework to investigate both lateral and vertical geometry of the potentially buried archaeological features (Conyers and Goodman, 1997)

Figure 3: The Church of St. Mary Magdalen in Rennes-Le-Chateau.

Results and Interpretation

The diagnostic GPR response to many buried items is a hyperbolic shape (inverted U) on the radar record. The top of the hyperbola and the shape of the tails aids in locating the subsurface feature. Of the lines collected in the project, a selection of preliminary results will be presented.

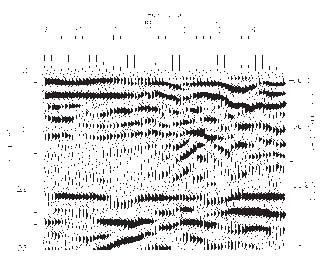

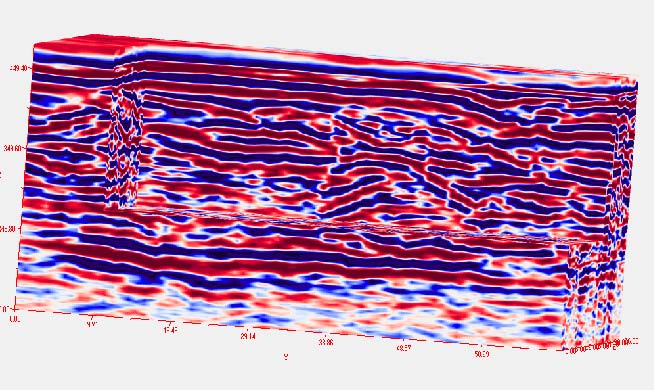

Tour Magdala

A GPR survey was conducted within and around Tour Magdala (Figure 2). The survey was carried out to image any features that may be located beneath the tower floor or around its base (outside). Both the west and north walls of the Tour Magdala were surveyed using 200 and 450 MHz antennae. Results indicate the tower is built on the local bedrock with possible surface and subsurface disruptions in the local stratigraphy. Data for 3-D cubes were acquired in the cellar of Tour Magdala. The GPR transects were collected using 450 and 900 MHz antennae with data points collected every 0.05 m and 0.025 m respectively. The dimension of the grids were (1) 3.7 m x 3.7 m (450 MHz; Figures 4 and 5), (2) 1.7 m x 1.7 m (450 MHz), and (3) 1.7 x 1.7 m (900 MHz). The GPR images show a hyperbolic feature that can be followed across several parallel lines, which may indicate the possibility of a buried feature (Figures 4 and 5).

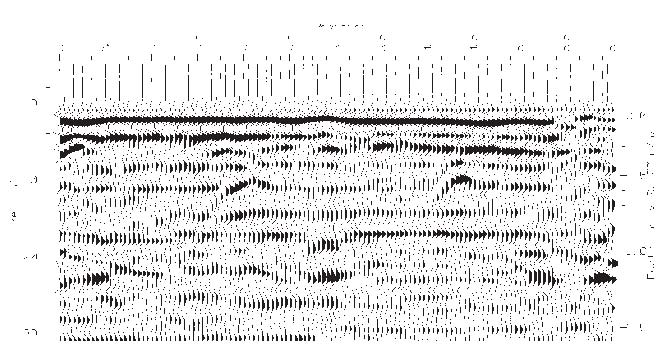

Church of St. Mary Magdalen

A high resolution GPR survey was conducted within the Church of St. Mary Magdalen (Figure 3). The survey was carried out to image any features that may be located beneath the church floor. Within the Church, the data for 3-D cubes were acquired along portions of the lower and upper church floor. The GPR transects were collected using 200 and 450 (see Figure 1). The profile shows the local bedrock (horizontal) layering at approximately 1.1 m depth. Above the bedrock layering at position 2.3 m is hyperbolic feature (diffraction) that is prevalent for several GPR lines indicating a feature potentially different from surrounding materials.

Figure 4: 450 MHz profile collected in the cellar/basement of Tour Magdala (see Figure 1). The profile shows the local bedrock (horizontal) layering at approximately 1.1 m depth. Above the bedrock layering at position 2.3 m is hyperbolic feature (diffraction) that is prevalent for several GPR lines indicating a feature potentially different from surrounding materials.

Conclusions

1. GPR datasets collected within and around the Tour Magdala revealed the subsurface structure along the base and within the cellar/basement of the tower. Results indicate a possible buried feature, which will require further work to identify.

2. GPR data were collected within the Church of St. Mary Magdalen, Rennes-Le-Chateau. France. The resulting GPR datasets reveal the internal structure of the church floor and a possible burial crypt(s), involving possibly one but probably at least two sepulchers.

3. The GPR images presented indicate 3-D imaging is an effective means of detailed subsurface analysis within these archaeological settings. 3-D rendering makes spatial associations easier to visualize.